“They raped me in front of my father. I was too scared to even make a sound. They threatened to kill us both,” said a 24-year-old Tigrayan woman, Simret*, who now lives in Qadarif refugee camp in Sudan.

Before the war in Ethiopia’s northern region of Tigray began, she lived in Humera, a town located in contested territory between the Tigray and Amhara regions. In early 2021, when she was attacked, Humera and the rest of Tigray were under the joint control of Ethiopia’s federal government, militias from the neighboring Amhara region and Eritrean allied forces.

In November 2020, following months of tension between the national ruling party, led by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, and the Tigray region’s ruling party, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), Tigray’s regional government rebelled against the federal government. Their efforts were largely unsuccessful, and their soldiers were routed out of the area after a few weeks of war with the Ethiopian national army and its allies.

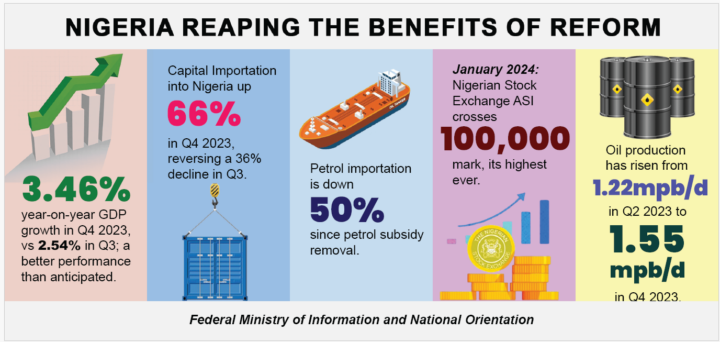

Between February and April 2021, when the state was in control of the Tigray region, over 1,288 cases of sexual violence were registered in the regional health facilities, according to Amnesty International. Many survivors, however, told Amnesty that they had not visited health facilities, suggesting these figures represent only a small fraction of rapes in the context of the conflict. The Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism (CCIJ) contacted Amnesty to request additional data about sexual violence in Ethiopia, but the organization could not provide it.

In this investigation, CCIJ also interviewed Dr. Fasika Amdeslasie, who was head of the Tigray health bureau during the early months of the war. He says his office received 1,772 sexual violence cases between Nov. 3, 2020 (the start of the war) and June 10, 2021.

The uptick of sexual violence survivors coming to hospitals for care was the first indication that the soldiers who were running the town were raping women on a massive scale. Since then, evidence has only mounted in reports by the media, human rights groups and a UN commission formed in December 2021.

The Ethiopian government says it has held some of its soldiers accountable for rape and other war crimes in the conflict, even though it minimizes the scale and systematic nature of the sexual violence. “[D]ozens of our soldiers have been sentenced to serious, serious penalties, some including to life in prison,” Gedion Timothewos, attorney general of the Ethiopian government, told the BBC in August 2021.

He did not say whether the prosecuted included members of the regional Amhara militia who fought on the government side. In CCIJ interviews with more than a dozen survivors and witnesses, Amhara militiamen and Eritrean soldiers – in addition to federal government soldiers – were accused of rape in western Tigray.

Timothewos also minimized the scope of the sexual violence perpetrated by government soldiers. He said the Ethiopian government had conducted its own investigations on the ground and did not agree with the conclusion that the rapes were systematic. “There are sensationalized reports – very exaggerated and unsubstantiated,” he told the BBC.

A UN Commission of Human Rights report on Ethiopia found that, among many other abuses, sexual violence had been committed on a “staggering scale.” Before the commission’s report, the federal government’s own minister for women, Filsan Abdi, had resigned over what she called official efforts to suppress her ministry’s findings about abuses by the government and its allies.

The perpetrators were not only fighting for the Ethiopian government, however. CCIJ found even Tigrayan fighters committed retaliatory acts of sexual violence that amounted to weaponization of rape in other zones of this complex conflict.

Each group of perpetrators thus far has acted with near total impunity for the lasting damage they have inflicted on victims ranging from 13-year-old adolescents to elderly mothers. And although military hostilities appear to have ended with the November 2022 signing of a peace treaty by the Ethiopian government and the TPLF, the accord contains no calls for accountability from the rapists or resources to help rape survivors heal.

A 50-something mother, who was gang-raped along with her daughters in February 2021 by men she believes to be Amhara militiamen, said that their “lives are ruined.”

“We don’t have the same social life we had previously,” she added, before lapsing into a long silence.

THE COMPLETELY UNACCOUNTABLE PERPETRATORS

Ethiopia’s reluctant admission and limited prosecution might almost look like justice if compared to another state actor in the conflict: Eritrea. By many accounts, Eritrean soldiers led the charge in weaponizing rape in the conflict in Tigray.

Of the 13 survivors interviewed by CCIJ in this investigation, five said their rapists were Eritrean soldiers – compared to two who pointed to Ethiopian soldiers. Yet the former are accountable to neither the Ethiopian government nor the international community from which their country, often called “the North Korea of Africa,” is isolated.

Simret says her attackers wore the uniform of the Eritrean army. “They did not hide their identity in the first place. They presented themselves as Eritreans,” she explained.

Another person who fled Humera in those months, a 17-year-old girl who was raped by nine soldiers, said, “I clearly remember… There were five Eritrean soldiers.”

The identity of the other four was unclear to her — she was not fully conscious during part of the ordeal. “Like a bad dream, I can only remember there were four, and [they] spoke Amharic [the official language of Ethiopia],” she recounted.

She said the attack happened in early February 2021 after the soldiers ordered her to walk to their camp. “I was scared they would shoot me. So I obeyed. When we reached the camp, they ripped my clothes and took turns gang-raping me,” she said.

The girl alleges that in mid-April 2021, she and other displaced people from Adi Goshu in western Tigray reached Humera. “They stopped us, let others go and ordered me to stay. Then they forced me into a nearby house – and that is when they raped me.”

Back in Adi Goshu a few days earlier, a 31-year-old woman was returning home from a local church when she was accosted by five soldiers she identified as Eritrean. “They were stationed in our neighborhood,” she explained. “They forced me into a house and gang-raped me.”

Reports by human rights organizations and other observers also prominently name Eritrean soldiers as major perpetrators of sexual violence in Tigray. One in three of the Tigray sexual violence incidence reports logged on the humanitarian data exchange, a data repository run by the UN Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, names the Eritrean Defense Forces soldiers as perpetrators. The incidents reported in this repository are collected from open source, public reports and do not represent the total number of all sexual assaults in Tigray.

VENDETTA IN A DECADE-LONG HOSTILITY

The circumstances that led to Eritrean soldiers fighting a war between the Ethiopian federal government and one of its own provinces are rooted in a decades-long relationship between Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki and the TPLF.

It dates back to Eritrea’s armed struggle for independence from Ethiopia, which the TPLF supported – although their alliance was on and off even then. Together, they defeated Ethiopia’s socialist regime in 1991. Eritrea broke away and, leading an alliance with other Ethiopian rebel groups, the TPLF took power in Addis Ababa.

Prior to secession, the boundaries between Eritrea and Tigray were of little consequence, since both were administrative regions of Ethiopia. Post-secession, Afwerki laid claim to an area called Badme, which the TPLF saw as part of its home turf – Tigray.

With the military might of the Ethiopian government it now led, the TPLF went to war with Eritrea in the 1998 Eritrea-Ethiopia border war, setting off years of hostility between the two former allies.

The Algiers agreement, signed in 2000 between the Eritrean and Ethiopian governments, ended active hostilities. The territorial issue was forwarded to the Hague boundary commission, whose ruling favored Eritrea. Yet the TPLF-led Addis government refused to hand over the territory ruled for Eritrea.

Under the pretext that this impasse left the possibility of war with its neighbor ever present, Afwerki, who is still ruling Eritrea, indefinitely extended military conscription for men in his country.

Ethiopia’s current prime minister won the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize for normalizing relations with Eritrea, but when what he initially called a “law-and-order operation” in Tigray escalated into full blown war, Eritrean soldiers joined the war.

Their battlefield conduct would look a lot more like a long-term political vendetta than routine law enforcement.

RAPE AS A WEAPON OF WAR

Multiple reports have emerged of Eritrean troops subjecting women and girls to sexual violence, but one incident, in particular, highlights the brutality of their alleged crimes.

In March 2021, a video of a young Tigrayan mother, who had reportedly been raped by 23 Eritrean soldiers, circulated widely on social media. It showed doctors removing long nails, pieces of plastic and stones from her body.

Chouchou Namegabe, a Congolese campaigner who has urged the International Criminal Court to classify rape as a weapon of war, recognizes the extremity of the sexual violence inflicted on the woman in the video. They are sending “a message to the enemy – they want to show victory in the woman’s body,” she says.

“In Congo, at first, we thought it was for a sexual need. But later we saw it was not,” Namegabe explains. “They [the perpetrators] want to inflict as much suffering as possible.”

Katrien Coppens, the executive director of Dr. Denis Mukwege Foundation, a foundation formed to end rape as a weapon of war, has identified common patterns which help distinguish between weaponized rape – a war tactic which uses rape to humiliate and destroy enemy forces – and rape by rogue troops.

In weaponized rape, she says, there are victims of all ages – including the elderly and children. The rapes are usually gang-rapes and carried out en masse. They also include a disturbing level of violence, such as cutting of breasts or other private parts of the body.

The rapes may include an element of torture. They often are carried out in front of family members or in public areas. And the perpetrators routinely use ethnic or otherwise derogatory slurs.

Coppens says, “Unfortunately, in almost any war, sexual violence is used as a weapon, because it is effective in causing terror and because of the shame associated with it in almost all cultures.”

“The trauma,” she adds, “lasts for generations.”

During interviews with CCIJ, we learned the victims in Tigray were subjected to many of these same patterns of weaponized rape. The testimonies in this investigation reveal the troops had targeted women and girls of all ages – from 13 to 65. Of the 13 victims interviewed, 12 of them said they were gang-raped. Four victims said they were gang-raped in front of their close family members.

Amdeslasie, who was head of the Tigray health bureau, also confirmed that whether committed by Eritrean soldiers or others, the sexual violence that happened in Tigray during that period had the hallmarks of weaponization.

“Almost all of the cases were gang-rape. The targets were women and girls in all age groups, from 6 years old to very old women. Religious groups, including monks and nuns, were targets. The abusers used ethnic slurs,” said Amdeslasie.

“There was also sexual slavery. A group of soldiers would hold captive dozens or more women in their military camp, repeatedly gang-rape them for weeks and then throw them [out] or kill them when they got very sick,” he added.

“Some of the victims say while they gang-raped them, the soldiers would say to them they are cleansing their Tigrayan blood,” Lewam Gebreslasie, a nurse treating rape survivors in Qadarif refugee camp in Sudan, told CCIJ.

OPTIONS FOR ACCOUNTABILITY

The Eritrean government has shown no indication of remorse, let alone any intention to hold its soldiers accountable, for weaponizing rape against Tigrayan women.

The Ethiopian government also appears unwilling to extend accountability beyond what it says it has already done. This October, it dismissed the UN human rights experts report, which found that its national army, allies and opponents committed violations, including the use of rape as a weapon of war – a form of war crime.

And though the Ethiopian government and Tigrayan forces signed a peace treaty in South Africa this November, it made no mention of providing justice for the victims of rape and other forms of sexual violence.

However, all of this does not mean that survivors of the documented abuse must go without accountability, says human rights advocate Dr. Ewelina Ochab, co-founder of the Coalition for Genocide Response. The organization has been calling for the UN to create a mechanism for evidence collection and preservation – and to include a special focus on the issue of sexual violence in its mandate.

Ochab also argues for building coalitions and consortiums across organizations working on justice and accountability for Ethiopia. “If we can learn anything from recent cases of atrocities, for example, those perpetrated by [Russian leader Vladimir] Putin in Ukraine, it’s that joint action towards justice and accountability can take us far,” she says. Though in their investigative infancy, at least 18 countries have initiated investigations of Russian abuse in Ukraine, and there is hope that accountability may follow.

But Ochab thinks there are other options – including “an ad-hoc or hybrid tribunal.” Ad-hoc international courts are temporary tribunals that focus on specific crisis situations, such as the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR).

Both were established by the UN Security Council to prosecute persons responsible for genocide and other serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of these two countries between specific dates. According to the UN, since its opening in 1995, the ICTR has indicted 93 individuals responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law, including high-ranking military and government officials, politicians, and religious and media leaders.

“The fact that the UN commission has now stated sexual violence has been perpetrated in the Tigray war… is an important step towards establishing ad-hoc courts. In good precedents, like Rwanda, there were similar steps before the establishment of ad-hoc courts,” says Ochab.

She also urges other countries to consider turning to their domestic courts by employing the universal jurisdiction principle, which allows countries to claim criminal jurisdiction over a person regardless of where the crime was committed. It is typically applied in extreme cases of genocide, torture and other war crimes.

One recent example is former Ethiopian official – Eshetu Alemu – who participated in ordering the execution of 75 people and other violations during the 1970s. In 2017, he was sentenced to life in prison in the Netherlands. In 2022, an appeals court upheld his conviction and life sentence.

Similarly, in recent years, Swiss courts have tried alleged perpetrators of war crimes in Liberia’s civil war under universal jurisdiction. On June 18, 2021, the Swiss federal criminal court sentenced Alieu Kosiah, a former commander of Liberia who participated in systematic killings, sexual violence and other war crimes in Liberia, to 20 years in prison. Kosiah has appealed and hearings are scheduled for January 2023.

Ochab says any country with expertise in prosecuting under this principle should take action. But there are challenges in invoking it, too. “Prosecutors would need credible and comprehensive evidence, which is currently hard to come by since Tigray is blockaded by the Ethiopian government from the rest of Ethiopia and the world,” she explains.

IMPUNITY BEGETS IMPUNITY

The sexual violence in Ethiopia’s conflict did not stop in Tigray, and the perpetrators were not limited to federal forces, Amhara militia and Eritrean allies. During their advance to neighboring regions of Amhara and Afar, the Tigray fighters also committed sexual violence in retribution for abuses committed in their homelands.

Abdi, the federal government minister for women who resigned, told the Washington Post that she believes these rapes would have been far less likely if there had been accountability for what the government forces and their allies had done in Tigray earlier in the war.

While CCIJ could not obtain comprehensive data on the scale of retaliation, doctors in major hospitals in Amhara estimate they have treated hundreds of victims of rape. And the humanitarian data exchange has logged at least 26 incidences of rape in Amhara and two in Afar, in which TPLF fighters have been named as the perpetrators.

Meanwhile, Amhara regional government officials told Amnesty International that more than 70 women alleged they had been raped in Nifas Mewcha, just one town in Amhara. In its own investigation, Amnesty found 16 rape victims in Nifas Mewcha.

Mihret* is one of the victims of that retaliatory TPLF rape campaign in Amhara. Her ordeal began on the afternoon of Sept. 1, 2021, when fighters from the Tigray army came to her village, Keno. Six soldiers barged into her house, where she also sells coffee, and gang-raped her, she says.

Over the next four days, other Tigray fighters continued to gang-rape her. According to her doctor, Mihret now suffers from a major depressive disorder and has tried to commit suicide several times.

In Chenna, another village in Amhara, several women were gang-raped, including Aynalem*, a 25-year-old woman who said she was gang-raped by three Tigray fighters on Sept. 2, 2021. During the attack, she told CCIJ, her abusers beat her and humiliated her with degrading ethnic slurs. Though she became pregnant following the assault, she managed to get an abortion.

THE AFTERMATH

In the dusty deserts of Sudan, tens of thousands live in makeshift shelters in sprawling refugee camps. Data from the United Nations refugee agency shows that more than 70,000 refugees and asylum seekers in Sudan are from Ethiopia. Among these refugees are survivors of sexual violence.

Unlike other refugees, they tend not to socialize much. They also don’t share their traumatic experiences, except with fellow rape survivors.

A few, however, did speak to CCIJ. Though they wildly varied in age, they all shared disturbing similarities of the brutality they were forced to endure.

A 65-year-old mother, who used to live in the town of Adebay, said she fled her hometown in February 2021 after being gang-raped by six militiamen. They spoke Amharic, and she believes they were part of the regional Amhara militia which fought on the side of the government in western Tigray.

“I was in my house. Suddenly a group of militiamen came to the neighborhood, terrorizing people in house-to-house searches… I begged them to leave me, saying I am very old. But they did not stop,” the mother of three said, before bursting into tears.

Today, she carries not just the horrific memory but shame too. She says her children, who are all adults, don’t know what happened to her. “How can I tell them? What happened is shameful to even think about it to myself.”

A 37-year-old former employee of the Ethiopian government is still in disbelief that it was soldiers of the same government she worked for who violated and scarred her for life. She said she was raped during a house-to-house raid in early January 2021 in the town of Adi Goshu.

“The [federal] soldiers were going from house to house, searching for supporters of the TPLF. I explained to them I am not a supporter and even showed them my office ID. They slapped my face and then took turns raping me,” she said.

A 21-year-old woman still blames herself for her brother’s murder. “He would have been alive if not because of me,” she said. The woman explains that in March 2021, soldiers, who she believes were Amhara militiamen, came to Adebay where she lived.

“They came into our house and started looting. They did not stop there. They raped me. My brother tried to fight them in defense of me, but he could not rescue me. Done with the rape, they pulled him out and shot him.”

A 52-year-old mother, who also fled from the town of Adebay, mourns the life she and her daughters once had. She says that on the night of Feb. 21, 2021, nine soldiers, who she believes were Amhara militiamen, barged into her house, demanding she give them jewelry and money, which she did.

“They were about to leave, taking the jewelry, but then three of them suggested rape. I begged them to do whatever they wished to me, but to leave my daughters. They took turns raping my daughters, who are 25 and 19 years old – and then on myself.”

In the refugee camp, she says all three of them have been receiving treatment for trauma.

Back in Tigray, where the rape campaigns first started, Amdeslasie, the former head of Tigray’s health bureau, says that a majority of the survivors who showed up at hospitals had signs of serious mental illness. “PTSD was very common. There were suicidal attempts,” he said.

Others showed signs of depression and dissociative disorders. “Some of them don’t know themselves. They have developed madness,” he said.

Gebreslasie, the nurse treating rape survivors in the refugee camp, says she is seeing many of the same symptoms among her patients. “They isolate themselves. They think everybody knows about [what happened to] them.”

Last October, she says a 15-year-old girl even hanged herself after being gang-raped in the town of May’cadra by four Amhara militiamen.

For those who survive and are now living in the refugee camp, the only way forward is to focus on recovering from their physical and psychological wounds. But, they all acknowledge, the memories of the brutal gang-rapes will likely stay with them for years to come.

*The names in this story have been changed to protect the victims’ identities.

This investigation was produced with the support of the National Endowment for Democracy and originally published by the Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism (CCIJ).