They are not the natives of the streets holed-up under bridges. They are not the major fragments of the globe. They are necessary. They are part of our existence. [Rewriting Sola Owonibi’s “Homeless Not Hopeless”]

When I was much younger, and I saw women walking in the day or night with babies strapped to their backs and pieces of tied clothing on their heads, I would think they were accidental human beings who just fell from the sky and started living in a foreign place. Are they homeless? Where have they come from? What could be in those loads they carry on their heads? I would ask myself.

In an open space at the Ikorodu terminal bus stop in Lagos on Tuesday afternoon is a line of street beggars, men and women, boys and girls, old and young. Beside them are pieces of loaded clothing which seem to be all they’ve got in life.

Amina Mumuni’s* life is torn between Katsina and Lagos. She’s been divorced. She said her husband handed her “a note of divorce” for committing no crime in 2020. She’s had eight children, including a set of twins, but two have died in the north.

“My husband divorced me by simply writing me a note of divorce. You know, our culture is different from your own. I had committed no crime; I did nothing. I was the eldest wife. After having six children for him, he married another woman. There was nothing I could do,” she said.

Since then, life has been hard on her, knocking hard on her and her children. In October 2021, she came to Lagos, hoping that things would turn around for good. Now that she bears the burden of her eight children, all in Katsina State.

“There are no opportunities for me. I could have been buying and selling petty, petty things or learnt tailoring or catering in the north. But where’s the money? Where’s the support system?” She asked.

COME RAIN OR SHINE

Mumuni sits on a concrete begging alms under the skin-biting sun. She’s a resident of Subuwa Local Government in Katsina State. She would come very early every day to eke out a living not only for herself but also for her children. She says her children school in Katsina and that she frequently sends them money from the pittance.

“I’ve had six children, including a set of twins. They are doing well in the north, in Katsina. I came specifically from Subuwa LGA in October 2021,” she said. “I took my destiny and the lives of my children into my hands. My children stay in the north; none of them is here with me begging alms. I do occasionally send money to them when I visit Lagos every four months.”

On Wednesday morning, at 10:52 am, Mumuni walked into the rain to beg at the terminal spot. She stays under the rain, not covering her head, save with the hijab, so much so that the drops of rain are frantically dropping on her head. Behind her is a woman, this one, with a child covering her head with a long blue nylon.

Eventually at 7:28 pm, I saw them, all of them, old and young, walking in a rank and file. Women only, with pieces of luggage carefully wrapped and tied up on their heads and with strapped babies protruding on their backs, I saw. I walked from behind them into the groping darkness, stepping into potholed muddy water. Only the women, old and young, were walking through narrow passageways connecting four separate streets – Olaketu, Imole Close, Onisigida and Okeyemi – all in Ikorodu.

The scary shadow of the darkness was dowsed by Yoruba makeshift sellers screaming that they be more orderly. To the Yoruba sellers, the sight wasn’t strange.

At 7:45 pm they got to the place, the savannah-like place aboding these street beggars. Where they call home is a garbage site, but for them, a luggage site, a refuge for the refugees. Somehow, three dead structures have been survived divinely so that these beggars now occupy exclusively two debris-filled, stench-steeped apparent graveyards. It seems not to bother them, the deadly smell, resurrected by the morning rain.

In a corner of the house a voice is heard, a Yoruba voice, mimicking some noble words of the Hausa-speaking residents. They appear to have coexisted peacefully in this particular ragbag building construction, the only Hausa family and the Yoruba, if not for the derisive remarks of the latter, which the former obviously take inoffensively. Behind the voice is a dark-complexioned twentysomething-year-old with a thick, creaky voice. He plays pun with a beggar’s words adding that one of her teeth would fall and he would take that tooth to one Baba for a ritual.

Then at 7:52 pm, I made a u-turn. One person, Mumuni, I had not seen, neither heard her voice. Halfway from the decrepit structure, I met with two load-carrying women. With her physique standing clearly out from the hijab and body-covering apparel, I could tell it was her, Mumuni. So I called her, Iya-Ibeji. Twice was she called until she responded, not by answering ‘yes?’ or ‘who is that?’ as common-practice in Lagos, but with a slow, suspicious turning back, as though looking back to behold her long-waited-for betrothed.

I approach her. Still surprised, she looks very deeply into my eyes overshadowed by the natural and my bodily darkness. Two surprises, I suspect, are ringing through her mind: who knows me as Iya-Ibeji in this Yoruba community and how did I get to know her dwelling? “Oga, it’s you. Good evening,” she said. She switches to Hausa gisting me with her friend. “Let me tell Oga, the landlord, you’re coming to visit us tomorrow morning,” she said, demonstrating the shortness of the landlord with her right hand. I’ve seen the ‘landlord’ Mumuni talks to me about thrice, at the begging spot. He and Mumuni are like the father and mother to the rest.

LIVING IN THE DEN OF ‘ARMED ROBBERY’

I managed to wake up 3:37 am after lots of turning-around and mosquito-biting in a mosque. This mosque, 18 kilometers from the popular Oriwu Central Mosque Ikorodu, from where I observed the sunset Maghrib prayer, was left open all through the day. The mosquito repellent I had used couldn’t repel the blood-starved mosquitos from perching on my skin. It was Thursday and I needed to get to Mumuni’s place, rather early.

I spoke with him, Ibrahim, the 20-year-old sharing a neighbourhood with a family beggar. “The two dilapidated houses were given to the Mallam begging alms at the garage,” he tells me, under the pretext of my renting a room. “The house has long been in that condition; it was a hotspot for armed robbery. Whenever the landlord needs them he’s going to tell them to leave. You can see for yourself that the houses aren’t good for living. I can tell you for free that some boys have been raided here today.”

Leaving Ibrahim, I learnt that one of housing structures the beggars live in is usually buried in water, the first floor, whenever there’s a heavy rain. Ibrahim noted that many of such beggars had lived through the two abandoned houses for years; however, he could not recall for how long. He seemed to be less older than the years the beggars had been living in Okeyemi Street.

I approach one, the defecated, debris-filled one, grossly stinking, very unlivable. But this is one house the beggars manage to pick up and drop pieces of their clothing, 7 in the morning and 7 in the night. Most of the beggars had not woken up; it was around 7:03 am. But I spoke with one beggar; she’s upstairs, to pour away a bucketful of overnight urine. “I’m looking for Iya-Ibeji,” I tell her. She points me to the corridor leading to Iya-Ibeji’s, that is, Mumuni’s, place.

Mumuni and I exchange pleasantries. She seems perturbed by my presence; that I visited so early, in the place she calls home. “Oga, good morning. I just dey prepare to come garage. How are you?” she said.

I asked her if there was anything I could do so she stopped begging. “Anything, Oga,” she tells me, “to do for me. I can buy and sell.” She looks productive, dark and gracefully thin, ostensibly in her early 40s.

“Is it safe for you living here? Do robbers attack you?”

“There’s nothing we can do, Allah. Me na just to sleep, wake up and look for help. Anything ko, whether food or money I see, Oga I’m okay.”

“Can I speak with the landlord you told me about?”

“He’s deaf. You can’t speak with him. You have to draw very close to him to understand his mind.”

“Do you pay a rent?”

“We don’t pay a rent. The landlord has been living here since. I met him here. I can’t say for the others. But somehow we seem to get along.”

“How did you know this landlord?”

“We just met, like every other person, at the begging spot you met us. That was in 2021. He introduced him to this place.”

“What do you normally carry on your head?

“Part of my clothes, Oga. I divide my clothes. To have something to wear when they steal the other clothes at home.”

“What does your husband do for a living? Does he support the children in any way?”

“My husband is a businessman. He gives whatever he can afford to the children.”

Minutes after Mumuni answered my last question on her husband’s occupation, a heavy sigh dropped on her chest. I caught sight of it, the heavy sigh. In a corner of the room are her small cooking utensils. The ceiling is peeling off opposite the bare floor. A line she hangs her clothes is hung over two stuck-out sticks from one end of the thatched roof to the other. The room is open, she tells me, to everything good she wishes herself.

‘SO THAT OUR PARENTS COULD BUY US RAMADAN CLOTHES’

“We came from Katsina to Lagos to beg for money so that our parents could buy us Ramadan clothes. We normally leave the begging spot 7, 8 at night; every day we are there. May God bless you. You will find favour with man and with God.”

12-year-old Sule tells me. I had stretched a handful of fruits to the folks on Tuesday afternoon. He didn’t tell me until Wednesday during the rain that his mother didn’t get anything from the small package. It was who-got-it-first kind-of survivalhood. We talked quite well in the Yoruba language as we saved our heads under the Ikorodu terminal roofing.

I didn’t know, he later told me, that his mother was breast-feeding a baby and she had approached me for benevolence.

Like Mumuni, Sule, and his family, came to Lagos in October 2021. He speaks Yoruba with a slight mixture of the Ogun State’s Ijebu version to me but switches to Hausa when interacting with his curious friends who questioningly want to know everything between us, or about me. He tells me he picks it up in the classroom, the Yoruba language, that his classroom teacher teaches them mostly in Yoruba.

Sule, the third child of the family of 8 in primary 4, says his father is a roadside mechanic and his mother a clothes-washing daily earner. “The money they gather in the north is not usually sufficient for us,” he tells me. “I’ve not eaten today. None of my parents has made any food provision today. That’s why I came to the begging spot whether I would get anything to eat.”

He says that his mother switches between begging and clothes-washing. “She has come here today,” he said, “but I can’t find her. She must have gone to meet with her friends.”

He adds that he treks a N500 transport distance to and fro to the government school very close to the begging spot. “I get to school every day at 9am. I leave home at 7,” he said, “but the teacher knows I come from a far distance, yet I’m flogged five strokes of the cane on my right palm. My legs ache after the long trek, so I come to the begging spot every other day.”

TILL DEATH DO US PART

On Monday, Mumuni had told me that “people with different problems from Arewa” begged at the Ikorodu terminal spot.

Surprisingly, a couple from Bauchi State at the begging spot. They had come all the way with their three children.

From the crowd of beggars I had brought them to the terminal roofing. Mumuni was with us, in blue hijab and green gown; she interpreted my questions to them, the couple, in the language they understood, Hausa.

“I came from Bauchi State to beg for food,” the wife said. “My husband and I have been in Lagos since the start of Ramadan fasting.”

“There’s a lot of hunger and poverty in my place. People who are hungry and praying for what to eat daily won’t listen to you. The three children we have are also here with us. We do the begging together but at the moment they’ve gone to play; you can’t see them. The government in Bauchi is not thinking about or taking care of us. But we manage to eke out a living from this corner.”

Yoruba woman onion-seller in-between) [Photo: Quadri Isiaka]

There’s a woman, Yoruba, sharing the same spot with this couple of beggars. On the ground are laid her onions; she sells them. She’s been selling there for more than seven years, she tells me, adding that she met some of the beggars begging there.

“I’ve sold onions at this terminal spot,” she tells me, “where the beggars stop every morning to beg alms for seven years. I actually met them begging there. Some of them have gone back to their states in the north. They’ve taken the terminal spot as their own place of work where they resume for their begging.”

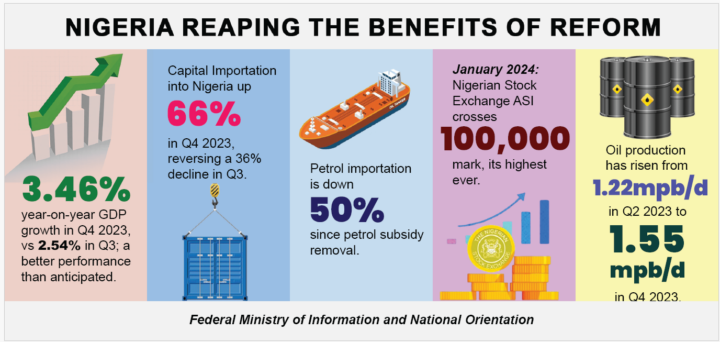

THE MULTIDIMENSIONALITY OF NIGERIA’S POVERTY

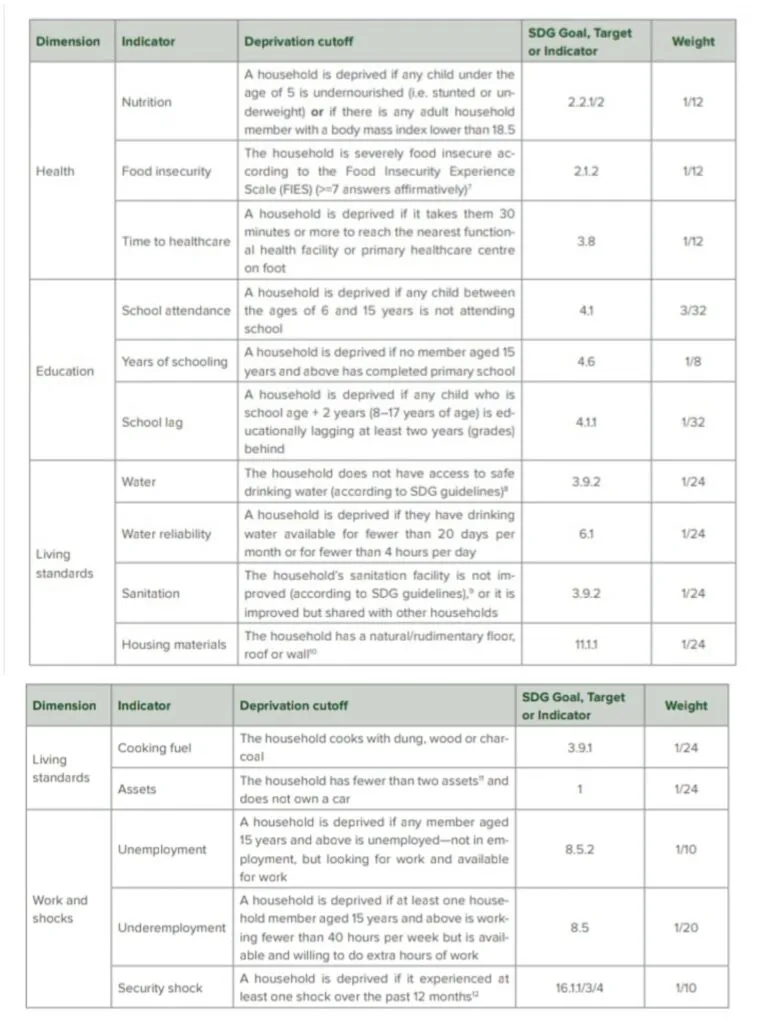

A country is said to be multidimensionally poor when there’s an intensity of deprivation in health, education, living standards, and work and shocks.

On November 17, 2022, the Federal Government, through the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), revealed that 133 million people (63% of slightly over 200 million population) are “multidimensionally poor”.

The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) (2022) survey states that out of 133 million poor people, 86 million people “live in the North, while 47 million people live in the South”.

Mumuni, Sule and the family couple I spoke with at the Ikorodu terminal, begging spot in Lagos meet the dimensional indicators of food insecurity, sanitation, housing materials, cooking fuel and assets.

The three of them have not had enough food to eat during the last 30 days because of money, so they can answer ‘yes’ to at least seven of the questions by the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) of the Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO).

They also do not have sewer or septic tanks. They have unimproved sanitation facilities. They live right in the surroundings they dispose faeces and urine. Cooking with woods or charcoals and having no fewer than two assets (cooking utensils and mobile phones, save Sule) also mean they have fallen below standard living.

In addition, while Sule is lagging four years behind educationally, Mumuni and the couple are not gainfully employed even though they are available for work.

It’s not enough having decorated campaign manifestos on poverty alleviation or releasing poverty index surveys without the willpower to reach out to the poor people in the street-roots and liberating them from their deprivation and oppression. Nigerian leaders must begin to walk their talk.

*Amina Mumuni is not her real name as she wanted her identity to be protected