Mixed reactions greeted Nigeria’s 2019 presidential elections outcome. The 2019 presidential election was expected to be a close race because the two main candidates are from the northern part of the country. But, in the end, the final result showed Muhammadu Buhari polling 56% of the total vote cast.

The 2019 elections featured a total of 73 presidential candidates but the real contest was between the incumbent of the All Progressives Congress and the former vice-president, Atiku Abubakar of the platform of People’s Democratic Party.

Despite Atiku’s perceived popularity and Buhari’s lacklustre performance during his four years as president, four key issues shaped the outcome of the election. Some of these had more to do with Abubakar’s weaknesses – such as being tainted as corrupt and bad calculations about voting patterns in the south – than Buhari’s strengths. But factors such as high levels of tensions in some parts of the country combined with a low voter turnout also had an impact.

The People’s Democratic Party was quick to condemn the elections. Atiku described the presidential poll as the “worst in 30 years”.

While the 2019 presidential election wasn’t perfect, it showed that democracy is gradually being entrenched in Nigeria.

The issues that mattered

First, the privatisation agenda of the former vice-president was not well received by Nigerians. Atiku promised to create jobs and sell the country’s oil corporation – The Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC). While selling the highly inefficient corporation might be a good idea, the part privatisation of the country’s electricity sector has not been successful and another privatisation drive raised concerns in many quarters. It was quickly rumoured around the country that the former vice president would sell the country’s prized asset to his associates forcing him to debunk the claim during several campaigns and interviews.

Second, political calculations especially in the South-West region of the country worked against the former vice-president. In 1999, when Nigeria returned to democracy after 16 years of military rule, there was an unwritten agreement between the power brokers that the presidency will rotate between the north and south for eight years each time. Although this is not constitutional, power has rotated between the north and south.

Since incumbent president Buhari had already completed a first term being a northerner, most people in the south believed that voting for another northern candidate would imply the north being in power for 12 years since it is assumed every candidate would wish to complete two terms of four years. This assumption put off many voters from the South against Atiku, who is also from the north.

Third, Buhari’s anti-corruption stance, coupled with corruption allegations against Atiku played a significant role.

In his book entitled, ‘My Watch’, former President Olusegun Obasanjo made several corruption allegations against Atiku who was the vice-president under his tenure. Although Obasanjo eventually endorsed Atiku, his unflattering characterisation worked against his candidacy as excerpts from the book were circulated widely by the media.

Buhari, on the other hand, was seen by many Nigerians as willing to curtail corruption in the country. This worked in his favour and probably earned him a second term.

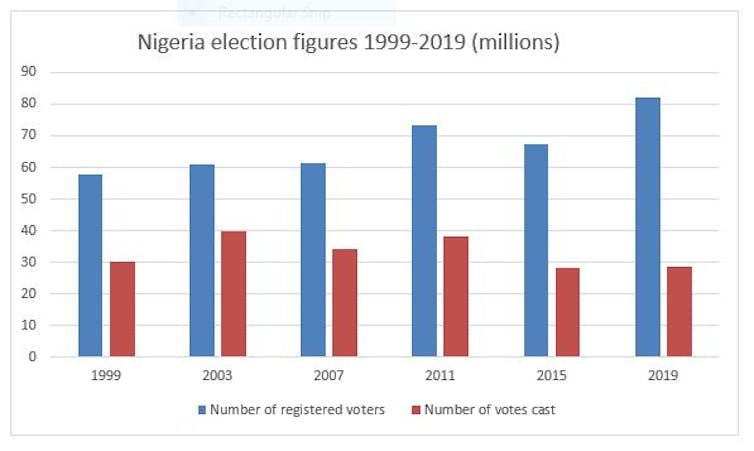

Fourth, the tense atmosphere around the country coupled with a heavy military presence in some parts limited voter’s turnout. This resulted in a record low of 35.6%. The numbers of registered voters rose from 57.9 million in 1999 to 84 million in 2019. But turnout continued a decline that’s been clear since 2003. In that year the turnout was 69.1%, four years later in 2007 it was 57.4%, in 2011 it was 53.7% and in 2015 43.6%.

The record low numbers affected both parties. But it affected People’s Democratic Party disproportionately. For instance, the party garnered 1.4 million votes in Rivers state in 2015 but only managed 473,971 votes this time round, losing about a million votes in a single state.

The low turnouts, especially in the South-south and South-East regions which are believed to be Atiku’s strongholds, also worked in favour of Buhari.

Free and fair?

Although pockets of election-related violence around the country resulted in the deaths of at least 39 people, the election has been described as free and fair in most usually volatile places.

In addition, there are two major indications that the elections were largely credible.

First, the outcome for several key individuals, such as incumbent governors, former governors and astute politicians, points to the fact that the will of the people prevailed in a great number of places. For instance, in the senatorial elections, the current senate president Dr Bukola Saraki, two sitting governors and six former governors lost to relatively unknown candidates. Those who lost had previously been classified as ‘untouchables’ and supposedly had guaranteed senate seats.

Second, the use of electronic card readers reduced the incidence of electoral manipulations that had characterised previous elections. Although the card readers were first used in the 2015 elections, the technology has been improved. This meant that there weren’t as many incidents of multiple and underage voting. (Figure 1 above shows the wide discrepancy between registered voters and actual voters.)

Prior to the use of card readers, the elections were fraught with irregularities and manipulations. This explains the fact that, despite lower numbers of registered voters, the number of votes cast were higher in the years prior to the use of electronic card readers. For example, this year 84 million voters registered, but only 29.3 million people were accredited to vote. This suggests that electronic voting has reduced electoral manipulation.

There’s another explanation – voter apathy. Nevertheless, the fact remains that it’s now more difficult to falsify election results.