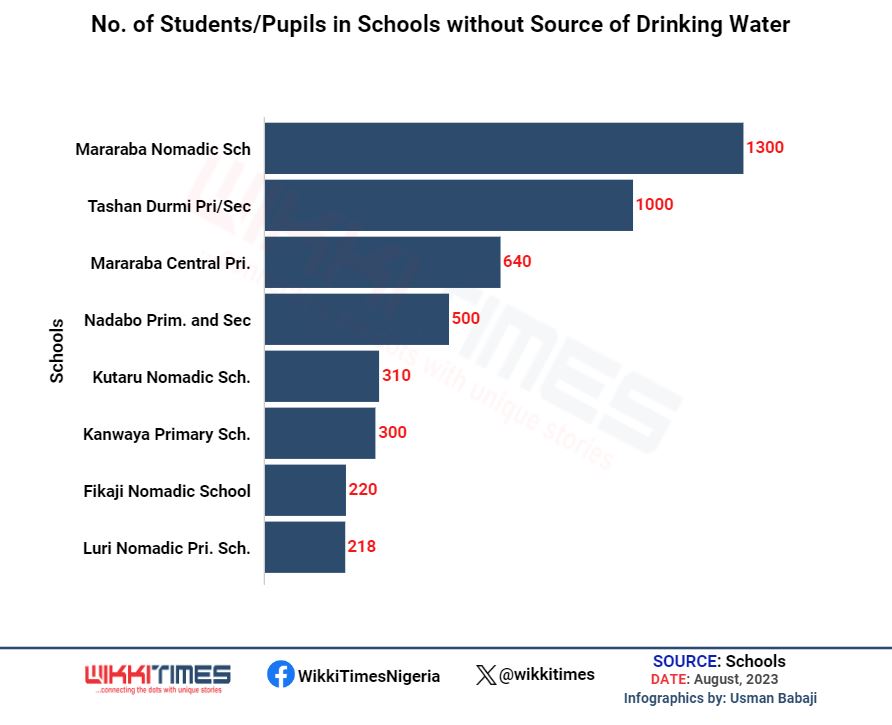

The lack of safe drinking water in various schools across Bauchi State is threatening the sustainability of basic and qualitative education (Sustainable Development Goal 4). It is crippling the attainment of the United Nations SDG Goal, being implemented by the Universal Basic Education Commission (UBEC) and the local actors. The WikkiTimes, in this report, documents how pupils are compelled to drink from nearby unsafe wells and streams, exposing them to waterborne diseases.

Pupils and students in several basic schools across Bauchi State lack access to clean drinking water. To douse their thirst, they have two options: either to drink unsafe water from nearby sources or go home and many would not show up in school again.

This implies teachers and pupils had no option but to rely on unsafe water sources and, in a few cases, depend on neighbours, exposing them to waterborne diseases. These were the realities in about eight schools across different local government areas visited by WikkiTimes.

Decades after its establishment, Nadabo Primary School and Junior Secondary School in Tafawa Balewa Local Government, Bauchi, still lacked access to drinkable water. This frustrates the students, staff, and locals in the community.

Close to the school is a nearby well constructed for worshipers. This ordinarily would have served as a better alternative. But, field findings by WikkiTimes revealed it contained worms and larvae. Thus, unsafe for consumption.

Therefore, parents in the community have concluded that the most common ailments among the pupils resulted from the regular intake of contaminated water in the school.

“After consistently battling with typhoid in my children, I had to warn them against drinking water in school,” revealed Musa Isah, a father of three pupils.

In another school, Alhassan Mohammed Abubakar, the Head Teacher of Tashan Durmi Primary School, could not hold back his concern. He said beyond waterborne diseases, the water scarcity has led to the dwindling number of pupils in school. He was quick to add that some would visit the school in late hours.

“It hinders their class attendance,” he told WikkiTimes, disgruntled.

In Nigeria, access to basic education is a natural right. It is vital to achieving a civil, learned, and egalitarian society, fostering Human Capital Development and nation-building.

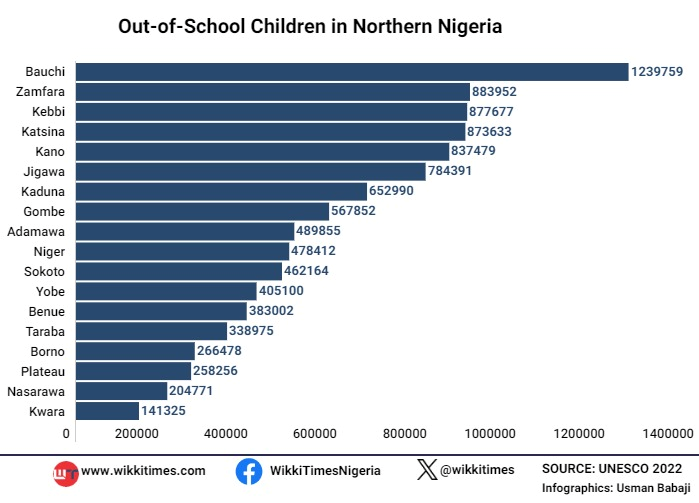

Section 15 of the Child Rights Act states, “Every child has the right to free, compulsory and universal basic education, and it shall be the duty of government in Nigeria to produce such education.” Still, reports have shown that not every child in the country is in school, especially in northern Nigeria. The adverse effect has been enormous, resulting in a low literacy rate and a drop in school enrolment.

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene also emphasises it is one of the essential needs to keep pupils active and healthy, especially during school hours. However, field findings revealed the reverse was the case in most locations visited in Bauchi.

THE BATTLE FOR CLEAN WATER IN BAUCHI SCHOOLS

Abdullahi Ya’u is the Community Head in Nadabo. As a leader, he made frantic efforts to push for his community’s development, but little was achieved.

Incidentally, Nadabo Primary and Junior Secondary Schools have remained the only community schools in the area. He said they have yearned for water in the community schools for long but no respite.

“It still gives us sleepless nights,” he told WikkiTimes.

Ya’u was interested in showing evidence of the abandoned project that would have resolved their water crisis. He took this reporter to a hand pump borehole, which was installed but never completed for more than 10 years. It was laying fallow as a waste.

“It was not completed and has never been used,” he explained.

The pupils’ immediate water source has been a well used for ablution by worshipers. Regardless, beyond drying up in the dry season, the community believes it is unsafe for drinking.

Ya’u lamented that despite other pressing challenges in the school, the lack of water denies hundreds of the pupils comfortable learning.

“We have leaking roofs and a lack of seats in the classes, but you know water is their wealth.”

Musa Isah is one of the residents and parent to three of the pupils. He corroborated the community leader’s position. According to him, typhoid became a common sickness among the pupils, and there was no other assumption than the water source in the school – the well.

Isah revealed the impact of water scarcity in the school is more pronounced during the dry season when all the sources dry up.

“They also find it disturbing to get water to wash their hands after using the toilet, which they use for food, and this is another thing that puts their health at risk,” he added.

Several other schools in the state share a similar fate, including Tashan Durumi Primary School in Jama’a District of Toro LGA, a school with over 1,000 pupils, according to Bashir Mohammed, a member of the school Management Committee (SBMC).

He said since the tap temporarily used to supply water to the school got damaged several years ago, they trek a distance to quench their thirst.

He added that on some occasions, pupils in search of water from a distant source miss lessons; this, he said, is negatively affecting their learning.

Alhassan Mohammad Abubakar, a teacher in the school who spoke to WikkiTimes, also validated Bashir’s submission. He identified the school’s major problem as, “…water, toilets, then the school structure and furniture.”

Abubakar disclosed how the school wrote ‘countless complaints’ to the responsible authorities without results. Beyond that, he disclosed how the pupils would often cross the highway (Bauchi – Jos Road) in search of water, and many would not show up at the school again, while others risked being hit by speeding vehicles.

“If we had water within the school, all these would not happen.”

It was a similar problem when WikkiTimes visited Kutaru (Kwanar Dutse) Primary School in Bauchi, the state’s capital. The pupils sometimes have to go to a nearby stream to drink water, according to the Headteacher, Abubakar Usman.

He lamented that due to the authorities’ neglect of the school, the pupils find it discouraging to attend daily classes. “They don’t come regularly; look at the school; nothing is working.”

This reporter only found less than 50 pupils during the visit.

In about five kilometres from Kutaru Nomadic Primary School were two other schools lined up at Mararaban Liman Katagum road. The Central Primary School Mararaba, with 640 pupils, had a failed borehole, and the Nomadic primary school, with over 1000 pupils combined with 300 students of the Upper Basic, never had a water source.

The SDG Goals 4 and 6 promote quality education, clean water, and sanitation. Besides, the UNICEF Global Development Commons believes there is a strong correlation between clean water and safe sanitation systems.

CHOLERA OUTBREAK IN SCHOOLS

Like Nadabo School, where diseases such as typhoid remained a major concern for parents, Luri Primary School, located in Tafawa Balewa LG and Mararaba Central Primary School (640 pupils) experienced a cholera outbreak. While Luri had over 218 pupils, Maraba could boast of 640.

The headteacher of Luri Primary School, Ja’afaru Adamu, told WikkiTimes that in 2021, the school recorded an outbreak of cholera among the pupils, compelling the school to suspend operation for a month.

Adamu attributed it to poor access to drinkable water and toilet facility in the school.

At Mararaba Primary School, several pupils reportedly contracted cholera. “Some of the pupils contracted cholera,” the school’s headteacher, Adamu Garba, told WikkiTimes.

Garba ascribed the dangerous disease to the absence of drinkable water coupled with the lack of toilets in the school.

SEVERAL SCHOOLS IN SAME DILEMMA

Fikaji Nomadic School, Dapasu, and Polchi Primary Schools, all in Tafawa Balewa LG, and Kanwaya Primary School in Toro LG, share water from nearby communities. They lack potable water within the school premises.

Abdulsalam Abubakar, a resident of Kanwaya, said Kanwaya primary school has no water, but the over 300 pupils share water with locals from a borehole built for the community.

Bello Musa, a teacher at Fikaji Nomadic School, confirmed that the pupils get water from a nearby water source. He agreed to the need for the school-owned water source. But, he argued, they have a more acute need.

“We want the school renovated more than anything else.”

Musa decried the decaying classrooms in the school. According to him, about 220 pupils in the school had no classroom to protect them from rainfall. These, he added, were affecting their learning.

Sources confirmed there were several other schools with similar tragedies of safe water inaccessibility across the 20 local governments of the state.

Data have shown that Bauchi accounts for the highest-burden of out-of-school children out of the 19 northern states, with over 1.2 million children not attending formal basic education institutions.

Meanwhile, Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) and Rights Activists have at several fora kicked against water poverty, especially as it prevents school enrolment. According to Humanium, an international NGO defending children’s rights, a child’s learning can be significantly impeded if their school lack drinkable water.

The group informed that children who drink dirty water are at greater risk of falling ill and, as a result, discard school.

“The right to water includes the right to quality water in sufficient quantity and the right to adequate means of sanitation to prevent diseases and maintain the quality of water resources,” it further explained.

GOVERNMENT REACTS

Mohammed Abdullahi, the Public Relations Officer of the Bauchi State Universal Basic Education (SUBEB), attributed the situation to an increase in the number of schools in the state. He said although the state government made some effort via the Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Agency (RUWASSA), several organizations are participating in water projects across the state. “We have several organizations supporting us in water provision.”

“There are charity NGOs, including foreign ones; WASH is constructing, RUWASSA is constructing, and SUBEB here is awarding water projects as well. But you know, schools in the state are many, but the state government is doing its best.”

Abdullahi argued that there are over 3,000 schools under the agency across the state, lamenting that the land terrains of some of the schools hinder the provision of water.

“…especially if you go to the Northern part of the state, the terrains of some places are not friendly. However, the state is doing its best.”

He frowned at the influx of children from neighbouring states due to lingering crises as another challenge that directly affected the schools.

The failure of the beneficiaries to protect the projects, he noted, against vandals and theft also remained a factor.

“It is one of the things the SUBEB Chairman, Dr. Abubakar Surumbai Dahiru, usually tells the beneficiaries—they should maintain and protect the projects.”

Gamawo – Bauchi Community Where Contaminated Stream is the Only Source of Water

Commenting on the school structures, he said the constructions received annual budgetary allocations, emphasizing that the present administration has built schools in hard-to-reach areas to provide conducive learning environments for children in the state.

However, the weeks-long efforts of WikkiTimes to reach out to the Bauchi State RUWASSA were unsuccessful, as the officers in the agency did not respond to the reporter’s request. The official letter addressed to the General Manager of the agency went unanswered.

The United Nations International Children’s Education Funds (UNICEF) declared that “access to clean water is a right, not a privilege” and emphasized that clean water must be prioritised.

Governor Bala Mohammed had, in 2020, spent N3.6 billion on official vehicles for government officials. In an investigation by Premium Times, Bala also allegedly awarded the contract to a company he is a director, clearly violating federal code of conduct laws and the state’s procurement law.

This report is produced with support from Civic Media Lab (CML).