By Busola Ajibola

A free, independent press that is not subject to any form of control, and censorship — by government, powerful individuals, or entities is integral to any functional democracy. The reason for this is not far-fetched. The most important role of the media, namely — news gathering, news dissemination, investigative journalism — cannot be efficiently performed by any other institution in a democracy. Investigative journalism is how the press acts as a check on governments and powerful entities to uncover corruption, human rights violations, abuse of power, other breaches of social contracts and reports to the public. Journalists maintain transparency in governance, and improve the knowledge of the public on how the policies and activities of government, its agencies and private entities impact their social, political and economic lives. And the press remains an important institution of democracy that has a clearly outlined ethical framework that must be adhered to for its practice to qualify as journalism — accuracy, truthfulness, and fairness in the service of public interest.

Despite its central role in democratic advancement, journalism, especially in Africa grapples with disruptions in revenue models by tech and social platforms, contributing to the challenge of poor remuneration, newsroom layoffs, and scanty investment in journalism business. Google confirms this trend in a public brief by stating that, “We agree that authoritative journalism is critically important to our democracies, and that the Internet and changing consumer behaviour has disrupted the historical business models of major news publishers”. But for not-for-profit models of funding newsrooms and investigative reporting, it is unclear if journalism, especially watchdog journalism would have been sustained this far — and yet, the not for profit funding model isn’t a sustainable way as donors may experience fatigue or choose to focus on new areas other than journalism.

Technology has always revolutionised media operations by offering innovative ways for news production and audience engagement. Media has always responded to technology of the time, transiting through print technology, radio, television and now internet and digital technology. Following that same trajectory, the media today, relies heavily on technological tools to conduct nearly all its operations (gadgets, emails and other communication channels, cloud storage system, AI automated transcription, AI spell checks, AI image generator/editor, AI text editing tools, etc.). Journalists and newsrooms also depend on tech platforms for information gathering and dissemination. Transitioning through such innovation at a very fast pace, for survival and relevance, the media itself qualifies to be defined as a technological phenomenon.

MEDIA AND TECHNOLOGY INTERFACE

This over-reliance of media on technology and its rapid evolution into a technological phenomenon intensifies the need to scrutinise press freedom in the era of digital transformation, with specific focus on Nigeria. In what ways do digital platforms envisioned as democratising forces host threats to freedom of expression and emerging concerns for journalists’ safety in the country?

Declaring the independence of Cyberspace in 1996, John Perry Barlow stated that the birth of the internet marked the creation of a world where anyone, anywhere may express themselves “without fear of being coerced into silence or conformity”; and advised governments that liberty cannot be warded off by erecting regulations — “guard posts” at the frontiers of cyberspace — they will not work in a world that will soon be blanketed in bit-bearing media.

Berners Lee, best known as the architect of the World Wide Web himself envisaged the internet as a space that encompasses “decentralised, organic growth of ideas, technology and society…where anything being potentially connected with anything was unfettered by hierarchical classification system”[1]

Online platforms, as envisaged by the gentlemen, became, and remain ‘global agora’ where citizens connect, air their thoughts, receive, and share information. They also became tools deployed by citizens to demand accountability from their governments — including coordinating protests like we saw during the #EndSars protest and the Arab Spring of the Middle East.

The Internet and social media platforms provided more affordable structures for amplifying the work of small and local newsrooms that ordinarily would have struggled with visibility and wouldn’t have been able to incur costs associated with physical newsroom operations and news production. In that regard, social media contributed to the emergence of a more diverse and inclusive media landscape.

Loads of threats capable of limiting press freedom however quickly accompanied the prospects offered by tech platforms. They include information disorder; digital surveillance of journalists and their loved ones; the weaponisation of cybercrime laws used to criminalise journalism; cyberbullying and trolling, internet shutdown and government clampdown on tech platforms; shadow banning of social media handles belonging to newsrooms and journalists; and payment dynamics between newsrooms and tech giants.

INFORMATION DISORDER

Social media platforms ferociously advance the spread of false, and misleading information that distort public opinion, election processes, and more sadly — public trust in credible journalism. The likelihood of people embracing views and information that aligns with their biases makes it easier for purveyors of information disorder to prey on them and further use them to amplify or multiply fake content. Deep fakes, AI-generated content, and other advanced technologies have also made it easier to reinforce fake news and distort facts. While the effectiveness of online platforms in disseminating good and reliable information cannot be overlooked, the threats they pose to free speech, access to quality information, media freedom and journalists safety must be pointed out addressed.

In the months preceding the Nigeria general elections, a study conducted by Dubawa showed that majority of contentious claims fact checked and found to be false originated from Facebook and that Twitter was primarily used to further circulate them. The same was trend was observed in the 2023 Liberia elections and in 2022 Kenya Elections. This not only highlights one of the ways social media threatens election outcomes but also how information disorder aggravates decline of trust in media as people consume both reliable and unreliable news sources on social media platforms.

‘Fake news’ have been identified to be free — meaning that people who cannot afford to pay for quality journalism, or who lack access to independent public service news media are even more vulnerable to information disorder. Second is that the spread of disinformation and misinformation is made possible largely through social networks and social messaging.

There are also emerging evidence of how journalists are targeted for identity theft to perpetrate fraud, or to spread information disorder. Kayode Okikiolu, a journalist with Channels Television published a disclaimer on Twitter warning the public about AI generated videos circulating online. In the video, his image and voice were falsely used to advertise drugs, games and so on. Similar challenges identified by media executives at a consultative forum organized by the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) include online trolling of journalists aimed at discrediting their work and mob/cyber bullying aimed at forcing journalists into self-censorship. Other cyber related threats identified by top Nigeria media executives include hostile regulations like the Cybercrime Act 2015, digital surveillance and economic challenges.

CRIMINALISATION OF JOURNALISM USING CYBERCRIME LAWS

Another digital security threat encountered by journalists is the criminalisation of their work through Cybercrime laws. The Cybercrime Act was introduced in Nigeria with the aim of establishing a legal framework to combat cybercrimes, protect critical national information infrastructure, and ensure cybersecurity. Section 24(1)(a) and 24(1)(b) of the Act criminalise the transmission of messages or content that is deemed offensive, indecent, or causes annoyance, among other broad and vaguely defined terms. The broad and undefined terms within the Act have been used to target, harass, intimidate, or arrest journalists like Jones Abiri, Agba Jalingo, Aiyelabegan AbdulRazaq and Oluwatoyin Bolakale, Luka Binniyat and a few other journalists leading to unfair prosecutions, detentions and the stifling of freedom of expression and press. This has continued to create a climate of fear and self-censorship among journalists to the detriment of investigative journalism.

Picture that captures Luka Binniyat’s health while in prison. Photo Credit: Gladys Binniyat

SURVEILLANCE & SPYWARES

The first plenary at #GIJC23 focused on the evil ramifications of surveillance ecosystems and how it impacts journalism. Journalists, like everyone else, use their mobile phones for storing information — both private and professional; performing official tasks; and connecting to the world. Sadly, their mobile phones are becoming tools with which they are targeted for attacks. In his keynote, Prof Ron Deibert of Citizen Lab, described the ability of spyware and surveillance companies to proliferate the privacy of journalists and their families as “god-like”. Most Spywares can silently activate phone cameras and microphones to listen in on conversations, and capture the geolocation of a phone — thereby helping intruders to determine the location of the owner of the mobile phone. The indiscriminate use of spyware also jeopardies the safety of journalists’ sources as their identity can be unveiled and their location traced.

Over the years, Citizen Lab has exposed targeted digital surveillance of journalists and members of civil societies through different spywares like Pegasus, Candiru, Quadream and so on. Journalists that are victims of such attacks as identified by Citizen lab include 35 journalists in El Salvador; Ben Hubbard of New York Times; and 36 others from Aljazeera. TheCable earlier this year reported multiple digital surveillance of journalists across Africa. They include Akpan, a Nigerian journalist who shared a pictorial documentation of citizens shot during the #EndSars protest on his social media handle; New Digest employee, Adebowale Adekoya; seizure of computers and gadgets belonging to Daily Trust and so on.

In 2020, Aljazeera reported that the Nigeria’s Defence Intelligence Agency acquired a surveillance instrument. The report indicted a company named Circle of helping state security agencies across 25 countries, including Nigeria, “to spy on the communications of opposition figures, journalists, and protesters.” In July 2021, Premium Times reported further that government allocated N4.8 (4,870,350,000) billion to the National Intelligence Agency (NIA) to monitor WhatsApp messages, phone calls, text messages and other communication channels.

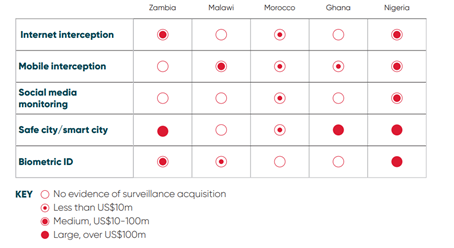

There is currently not much specific empirical data of surveillance patterns of journalists by government and powerful entities in West Africa. Research however confirms that African governments are collectively spending US$1bn per year on surveillance technologies and are using them in ways that are unlawful and/or violate the fundamental human rights of citizens. The report identified Nigeria as Africa’s largest customer, spending at least US$2.7bn on surveillance technologies in the last decade and stated that the spywares has been used on peaceful activists, opposition politicians, and journalists. This runs contradictory to Section 37 of the 1999 Constitution of Nigeria that guarantees ‘the privacy of citizens, their homes, correspondence, telephone conversations, and telegraphic communications. One of the dire implication of surveillance how it forces journalists and citizens into self-censorship and conformity and how this severely impede on freedom of expression and right to access information.

In an era where citizens’ identities are integrated into biometric technology during enrollments for immigration, national identity, international passport, drivers’ licence, bank accounts, the research raises a fundamental question of “what happens when the biometrics identification is turned off against a person on any of the platforms and what actions should be completed before such deactivation?”. The research highlighted the case of Omoyele Sowore, a Nigerian activist and former presidential candidate citing the deactivation of his biometric identification:

“The activist’s national identification card, permanent voter card, foreign passport, and driver’s licence were among the documents to be deactivated. Because the cards cannot be read biometrically, Sowore was then unable to use any of the above-mentioned IDs because they could not be read as a result of his biometrics being deactivated”.

It is scary to imagine what this portends for journalists fleeing targeted attack or harassment from one state to another, a country to another within Africa. Examples of loopholes that are used in justifying such unlawful interception are section 45 of the constitution and Article 7(3) of the Lawful Interception of Communications Regulation 2019 which permit the interception of citizens’ privacy in cases affecting national security, public safety, order, morality, or health.

INTERNET & SOCIAL MEDIA SHUTDOWNS

Other frequent methods that have been identified as means of suppressing freedom of expression and press are Internet and/or social media disruptions. Governments shut down the internet or make desperate attempts at regulating social media platforms in a bid to restrict information flow and limit public discourse. Identified circumstances where governments invoke internet shutdowns include active conflict, humanitarian crises, widespread protests, pivotal elections, or reactionary responses to sudden upheavals.

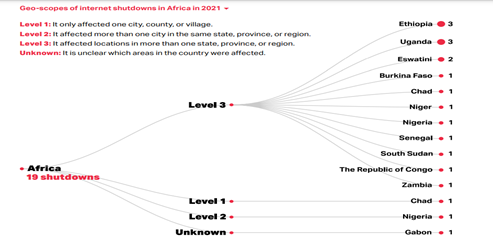

Internet shutdowns are also deployed as tactics to force people into using alternative platforms where surveillance and censorship are easier to implement.” Africa has been identified as one of the continents with most documented episodes of internet shutdowns over the years. In 2021, 12 African countries experienced internet outages 19 times as seen the infographic below. I have also curated at least 35 incidents of internet shutdowns across Africa between 2019 and 2023 in this drive and will continue to update it.

President Muhammadu Buhari, on June 4 2021 banned Nigerians from accessing Twitter (now X) for a staggering 7 months. In a fashion that exemplifies a recurring trend of human rights violations under the guise of safeguarding national security, maintaining public order, or upholding public morality, the government, through its then Attorney General of the federation Abubakar Malami justified the violation of citizens’ rights to own, establish, and operate any medium for dissemination of information, ideas and opinions guaranteed under S. 39 of the 1999 Constitution(amended) citing section 45 of the same constitution.

Nigeria, like several other governments across Africa have constitutional provisions that guarantee citizens’ right to freedom of expression. They are also signatories to regional treaties like Article 9 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and international treaties like Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights which states that everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression, including freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice

SHADOW BANNING, CYBERBULLYING & CONTENT MODERATION

After publishing a story that unveils the mismanagement of an appendicitis surgery that left little Chinazam with a life-threatening brain injury by a health facility belonging to Shell Nigeria, Fisayo Soyombo, an investigative reporter and publisher of Foundation for Investigative Journalism announced on X (formerly Twitter) that his twitter handle had been reported and risked being suppressed or suspended. His followers in various comments confirmed that visibility for the story was suppressed.

Shadow banning, where social media platforms limit the visibility of accounts or out rightly suspend social media handles belonging to newsrooms and journalists reduce their visibility, stifles them, hampers their ability to disseminate information, causing great impediments for the right to access and disseminate information.

WikkiTimes, an online media platform in northern Nigeria also reported that it encountered consistent cyber-attacks and social media trolling, including on Facebook where its pages are regularly reported and subjected to takedown requests. Between April and November 2022, the newsroom reported that its website was not only frequently attacked but taken down for several days on a few occasions leading to loss of data and published reports.

“In October 2022, Facebook brought down WikkiTimes’ Facebook page which had thousands of followers for violating its community policy. Despite sending several emails and appeals to Facebook, WikkiTimes lost the page. A month later, Facebook also suspended a new page WikkiTimes created after the platform published an investigative report. WikkiTimes regained access to their Facebook page weeks later by filling out a verification form.”

Victoria Bamas is the Editor of the International Centre for Investigative Reporting (ICIR), a Nigeria based newsroom. Her Twitter handle was verified as a journalist in April 2022 but was soon taken over and she was denied access. Victoria is unsure whether the access denial to the handle has specific relation to press freedom but according to her “I had to ask several people to report it and also reached out to someone I know who works with the platforms to get it recovered”. In November 2023, ICIR also battled spamming and website downtime due to too much traffic from bots. The attack occurred after the newsroom published this investigation.

This brings us to question of how online content are moderated. The dominant assumption among social media users is that online content moderation is automated through algorithms. The complex nature of human expression, encompassing context and nuance raises a question of how automated algorithms can effectively evaluate content shared online. Yet, shadow bans and suspensions are imposed on journalists and newsrooms by social media platforms because they are reported to have violated community standards and they are mostly deprived the right to fair hearing. This presents a challenge as journalists allege that bots and fake social media handles used for targeting social media handles belonging to journalists and newsrooms are used massively to report them.

PAYMENT DYNAMICS BETWEEN NEWSROOMS AND TECH COMPANIES

As mention in the early paragraphs, a severe impact of digital transitioning on media is revenue decline. One of the revenue models adopted by tech platforms are sponsored posts and adverts. What is not fair is that like every other user, newsrooms are required to pay tech companies to disseminate investigative reporting — despite the public interest nature of journalism and its core watchdog role in a democracy. Content generated by digital news platforms constitutes a vast amount of internet and social media content made accessible to the public online. Yet, tech platforms have continued to refuse the proposition that they should compensate local media for their content used on internet and social media.

In 2009, Rupert Murdoch stated that “digital companies profit when they surface journalists’ headlines and news snippets” and questioned the morality of tech platforms’ usage of news content belonging to newsrooms without contributing a penny to the production. A decade after, the Australian parliament passed the News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code that addresses the bargaining power imbalance between news media businesses and digital platforms. The law compels Facebook and Google to pay substantial sums — sometimes in the tens of millions of dollars — to news organisations whose headlines frequently appear on platforms’ pages.

Meta and Alphabet, the parent organisation for Facebook and Google have subsequently resisted attempts to comply with the law in full n Australia or even have it replicated in other countries. While some newsrooms in Australia for instance benefited from the law, the Special Broadcasting Service of Australia was shut out by Facebook after its received some compensation from Google.

In 2023, The Canadian Senate passed the nation Online News Act, also known as Bill C-18 — mandating Big Techs to strike fair compensation deals with local journalism outlets for news that is shared on their platforms. However, shortly after the passage of the bill, Meta responded by blocking news in Canada on their platforms, ensuring that people living in Canada were deprived access to news on Facebook and Instagram. Google, in the same fashion, threatened that it would remove links to Canadian news from “Google Search, News and Discover products. It also claimed that the bill will make it untenable for it to continue offering Google News Showcase products in Canada.

This is where we begin to interrogate the public or private nature of internet platforms. Should they solely exist as business or in the interest of humanity and thereby serve, first and foremost, the public? Where internet platforms shit out news organisations and thereby deprive the public the right to access critical information they require to make informed decision, should they not be held liable?

Africa is yet to experience such scenario where any of the Big-Tech deny news media access to publish news on their platforms. It is however time for newsrooms and publishers in Nigeria and other African countries to actively participate in the negotiations for adequate compensation for their content used on internet platforms. The Competition Commission of South Africa has shown leadership in setting up an inquiry on the issue. It affirmed that though Big Techs and social media platforms generate revenue through online advertising, traffic, engagement, and data collection, a significant portion of the traffic and engagement comes from content produced by news publications.

Findings from the inquiries further reveals that the practice of offering news snippets on internet searches and social media denies the publishers referral traffic as news consumption has shifted to many consumers simply browsing news snippets. This change in news consumption, according to the inquiry, adds value to internet search engines and social media platforms, allowing them to monetise data or advertising, and in so doing extract the benefits of copyright content from newsrooms and publishers. The nature of searches on internet and social media platforms also affords Big Tech dominant access to consumer data, which they in turn deny publishers and newsrooms full access to.

RECOMMENDATIONS

● While journalists continue to deploy fact-checking as a means of curtailing information disorder, Big Techs are urged to detoxify their platforms of algorithms that amplify disinformation. Nigeria and other African countries should to be priortised in this regards because of the evolving and fragile nature of their democracy.

● The Nigeria National Assembly’s Senate Joint Committee on ICT & Cyber Security and National Security & Intelligence on November 22, 2023 held a public hearing to review the Act. Part of the recommendations the committee is urged to consider is a review of section 24 and 38 of the Act ensuring that it no longer be used as a weapon to harass journalists or subject them to surveillance.

● There is a need to reign in the obsession of government and its agencies to surveillance. Also, surveillance capitalism embarked on by corporations that sell surveillance technology to governments and its institution should be checked. Surveillance practices without obtaining court order should also be explicitly prohibited by national and regional laws.

● The media and civic society should be at alert and establish a robust documentation framework of surveillance threats to be used in demanding legal accountability and remedy in cases of abuse. They should also advocate full implementation of data and privacy protection laws.

● The evident lack of transparency regarding the deployment of algorithms for content moderation, particularly in instances where the definition of these standards remains ambiguous is problematic. Such ambiguity raises fundamental questions about the fairness and accuracy of moderation practices, especially when they impact the ability of journalists and news outlets to disseminate information crucial to public discourse as seen with the case of WikkiTimes, FIJ and ICIR. There is therefore a need for greater transparency in the deployment and functioning of these algorithms. The process for evaluating online content and the basis upon which decisions leading to bans or suspensions are arrived at should be made public.

● Social media platforms should consider assigning distinct verification status to journalists and newsrooms, setting them apart from social media influencers, online celebrities, politicians, and other users. Given the public nature of journalism and its pivotal function in disseminating information, this distinction is crucial. Implementing such specialised verification for journalists and newsrooms serves multiple purposes. First, it acknowledges the unique responsibility and professional standing of journalists in the information ecosystem. Second, it aids in combating misinformation as it enables the public to easily identify and trust these verified handles for authentic news and information.

● By distinguishing journalists and newsrooms through a special verification status, social media platforms can contribute significantly to promoting credibility, accuracy, and reliability in the dissemination of information. This differentiation recognizes the distinct public interest role played by journalists while empowering users to discern and access authentic news sources more efficiently.

● Governments at national and sub-national levels are urged to commit to adopting UNESCO Guidelines on Regulating Digital Platform which provides established guides on how to address violation of free speech, access to information, censorship, and privacy concerns. In this regard, politicians and leaders alike should acknowledge that journalists are not adversaries but individuals performing constitutional obligation of accountability required for the protection of human rights and transparency in governance.

● The Federal Competition and Consumer Protection Commission (FCCPC), and/or other concerned agencies should conduct an investigation that can help shed light on the economic dynamics that exist between newsrooms and Big-Techs like Google, Meta, X, Apple News and so on. The investigation should track the impact of anticompetitive conduct and dominance of internet and social platforms, and how internet search engines and social media platforms benefit from news. The investigation should further determine how revenue generated from the searches can be fairly shared between news media and digital platforms.

● The Federal government of Nigeria should rally newsrooms and Big Tech in conversations on fair compensation as part of revenue generation means for media sustainability. This should be done bearing the complex boundary of journalism as a social enterprise and a business in mind. The preference should be an acknowledgement of journalism first a social enterprise that is not necessarily profit driven but requires intensive funding. Producing good journalistic enterprise in ways that preserve the utilitarian value of journalism — as a watchdog, agenda setter, and gatekeeper — is expensive.

● Beyond this, regional bodies like AU, ECOWAS should collaborate with governments in Africa, newsrooms, and Big Techs to establish a legislative frameworks similar to the News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code to address power dynamics between newsrooms and tech platforms — on issues of content use and compensation. Competition Commission of South Africa is setting a good example worthy of emulation by other national governments across Africa.

● Big Techs have a moral obligation to invest in local journalism across Africa by compensating newsrooms whose content they benefit from while also establishing more parallel funding support that can help sustain local journalism in Africa without impeding its independence. They need to be intentional about designing mechanisms that guarantee the safety of journalists living on the continent. These forms of support for local journalism in Africa is key considering the enormous resources the continent is blessed with, and the horrendous mismanagement of the resources by its leaders.